The Great Wen treated us to bright sunshine and blue sky when we emerged from Warren Street tube station. It made Tottenham Court Road look picturesquely scruffy rather than depressingly drab, but we didn't care - we were off to our first Palace of Delights: Waterstone's in Gower Street.

Having parked my non-bookish husband in the basement coffee shop with a latte and the Saturday paper, I wended (wound?) my way upstairs to the secondhand department, an Aladdin's Cave to a bookaholic whose purse is never big enough to buy all she would like. I was only constrained in my purchases by what we could carry, but I was delighted with my Catch of the Day (see end of post).

Having parked my non-bookish husband in the basement coffee shop with a latte and the Saturday paper, I wended (wound?) my way upstairs to the secondhand department, an Aladdin's Cave to a bookaholic whose purse is never big enough to buy all she would like. I was only constrained in my purchases by what we could carry, but I was delighted with my Catch of the Day (see end of post). until we reached our next Palace, the British Museum.

until we reached our next Palace, the British Museum. The BM's current blockbuster exhibition is The First Emperor: China's Terracotta Army but here lack of forward planning (viz. not checking to see if we needed to book) meant the only disappointment of the day (or an excuse to come back again soon). We won't make the same mistake with Hadrian: Empire and Conflict which opens on 24 July.

The BM's current blockbuster exhibition is The First Emperor: China's Terracotta Army but here lack of forward planning (viz. not checking to see if we needed to book) meant the only disappointment of the day (or an excuse to come back again soon). We won't make the same mistake with Hadrian: Empire and Conflict which opens on 24 July.And so, we retreated, chins quivering, to console ourselves with coffee in the lightsome and elegant Great Court

before heading to our favourite parts of the BM: the King's Library

and the Rooms containing Lindow Man, the Vindolanda Tablets and the Sutton Hoo Ship Burial.

After a brisk stroll down Charing Cross Road (so many bookshops, so little time), lunch was had in the National Portrait Gallery's rather poky basement caff, whose filthy cutlery we hesitated to complain about for fear of being responsible for a Pythonesque mass staff suicide.

Having recovered from this trauma, we ambled through the galleries in a roughly chronological fashion, but barely reached the 19th century before it was time to set off for the theatre. It was thrilling to see our history through the people who made it, and the NPG never fails to delight and enthrall. I should add that I'm a bit of a philistine where Great Art is concerned, rather like Tony Hill who memorably said in a recent episode of Wire in the Blood: "I don't know anything about art. I don't even know what I like." Hmm. I think I like Rembrandt and Turner and Vermeer, but I've no idea why. So the National Gallery round the corner from the NPG in Trafalgar Square is somewhere I know I ought to visit, but rarely do.

Our final Palace of Delights actually had "palace" in its name: The Palace Theatre in Shaftesbury Avenue, facing on to Cambridge Circus. Here it is in all its glory. rather like many-tower'd Camelot (although it was built in the 1890s by Richard D'Oyly Carte).

Spamalot was a hoot from start to finish, a panto for grown-ups, a comical send-up of musicals in general and a genuine olde rippe-offe of Monty Python and The Holy Grail, complete with the clip-clop coconuts, the Knights Who Say "Ni", the French Taunters and the added bonus of Always Look on the Bright Side of Life tacked on from Life of Brian, lo, even unto the audience singalong at the end. Oh, and the voice of John Cleese as God. We wondered how they would do King Arthur's dismembering fight with The Black "it's only a scratch" Knight. Ingenious. Side-splitting. Do see it if you get the chance.

Spamalot was a hoot from start to finish, a panto for grown-ups, a comical send-up of musicals in general and a genuine olde rippe-offe of Monty Python and The Holy Grail, complete with the clip-clop coconuts, the Knights Who Say "Ni", the French Taunters and the added bonus of Always Look on the Bright Side of Life tacked on from Life of Brian, lo, even unto the audience singalong at the end. Oh, and the voice of John Cleese as God. We wondered how they would do King Arthur's dismembering fight with The Black "it's only a scratch" Knight. Ingenious. Side-splitting. Do see it if you get the chance. Only make sure you don't get seats with the tallest man in the world sitting in front of you, and behind you the woman who does the world's loudest braying donkey impressions (was she part of the act?).

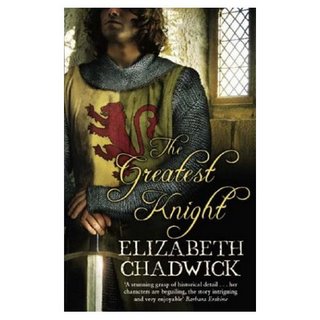

Only make sure you don't get seats with the tallest man in the world sitting in front of you, and behind you the woman who does the world's loudest braying donkey impressions (was she part of the act?).And finally, here's my Catch of the Day, all from Waterstones's Secondhand Department except for Paths of Exile which arrived in the post whilst we were out. And presiding over all is Henry, the Intellectual Indian Runner Duck. You can't see in the photo but he's wearing specs and is carrying a book and an apple. And a tag with his name on it on a piece of string round his neck. In case he get so absorbed in his book he forgets who he is. A bit like me, really.